Economics¶

This section provides a general discussion of the generalized Roy model and selected issues in the econometrics of policy evaluation. The grmpy package implements a parametric normal version of the model, please see the next section for details.

Generalized Roy Model¶

The generalized Roy model ([24]; [14]) provides a coherent framework to explore the econometrics of policy evaluation. Its parametric version is characterized by the following set of equations.

\((Y_1, Y_0)\) are objective outcomes associated with each potential treatment state \(D\) and realized after the treatment decision. \(Y_1\) refers to the outcome in the treated state and \(Y_0\) in the untreated state. \(C\) denotes the subjective cost of treatment participation. Any subjective benefits, e.g. job amenities, are included (as a negative contribution) in the subjective cost of treatment. Agents take up treatment \(D\) if they expect the objective benefit to outweigh the subjective cost. In that case, their subjective evaluation, i.e. the expected surplus from participation \(S\), is positive. I denotes the agent’s information set at the time of the participation decision. The observed outcome \(Y\) is determined in a switching-regime fashion ([21], [22]). If agents take up treatment, then the observed outcome \(Y\) corresponds to the outcome in the presence of treatment \(Y_1\). Otherwise, \(Y_0\) is observed. The unobserved potential outcome is referred to as the counterfactual outcome. If costs are identically zero for all agents, there are no observed regressors, and \((U_1, U_0) \sim N (0, \Sigma)\), then the generalized Roy model corresponds to the original Roy model ([24]).

From the perspective of the econometrician, \((X, Z)\) are observable while \((U_1, U_0, U_C)\) are not. \(X\) are the observed determinants of potential outcomes \((Y_1, Y_0)\), and \(Z\) are the observed determinants of the cost of treatment \(C\). Potential outcomes and cost are decomposed into their means \((\mu_1(X), \mu_0(X), \mu_C(Z))\) and their deviations from the mean \((U_1, U_0, U_C)\). \((X, Z)\) might have common elements. Observables and unobservables jointly determine program participation \(D\).

If their ex ante surplus \(S\) from participation is positive, then agents select into treatment. Yet, this does not require their expected objective returns to be positive as well. Subjective cost \(C\) might be negative such that agents which expect negative returns still participate. Moreover, in the case of imperfect information, an agent’s ex ante evaluation of treatment is potentially different from their ex post assessment.

The evaluation problem arises because either \(Y_1\) or \(Y_0\) is observed. Thus, the effect of treatment cannot be determined on an individual level. If the treatment choice \(D\) depends on the potential outcomes, then there is also a selection problem. If that is the case, then the treated and untreated differ not only in their treatment status but in other characteristics as well. A naive comparison of the treated and untreated leads to misleading conclusions. Jointly, the evaluation and selection problem are the two fundamental problems of causal inference ([17]).

Selected Issues¶

We now highlight some selected issues in the econometrics of policy evaluation that can be fruitfully discussed within the framework of the model.

Agent Heterogeneity¶

What gives rise to variation in choices and outcomes among, from the econometrician’s perspective, otherwise observationally identical agents? This is the central question in all econometric policy analyses ([4]; [8]).

The individual benefit of treatment is defined as

\[B = Y_1 - Y_0 = (\mu_1(X) - \mu_0(X)) + (U_1 - U_0).\]

From the perspective of the econometrician, differences in benefits are the result of variation in observable X and unobservable characteristics \((U_1 - U_0)\). However, \((U_1 - U_0)\) might be (at least partly) included in the agent’s information set I and thus known to the agent at the time of the treatment decision.

As a result, unobservable treatment effect heterogeneity can be distinguished into private information and uncertainty. Private information is only known to the agent but not the econometrician; uncertainty refers to variability that is unpredictable by both.

The information available to the econometrician and the agent determines the set of valid estimation approaches for the evaluation of a policy. The concept of essential heterogeneity emphasizes this point ([12]).

Essential Heterogeneity¶

If agents select their treatment status based on benefits unobserved by the econometrician (selection on unobservables), then there is no unique effect of a treatment or a policy even after conditioning on observable characteristics. Average benefits are different from marginal benefits, and different policies select individuals at different margins. Conventional econometric methods that only account for selection on observables, like matching ([6]; [23] ; [10]), are not able to identify any parameter of interest ([14]; [12]).

Objects of Interest¶

Treatment effect heterogeneity requires to be precise about the effect being discussed. There is no single effect of neither a policy nor a treatment. For each specific policy question, the object of interest must be carefully defined ([14], [16], [15]). We present several potential objects of interest and discuss what question they are suited to answer. We start with the average effect parameters. However, these neglect possible effect heterogeneity. Therefore, we explore their distributional counterparts as well.

Conventional Average Treatment Effects¶

It is common to summarize the average benefits of treatment for different subsets of the population. In general, the focus is on the average effect in the whole population, the average treatment effect (ATE), or the average effect on the treated (TT) or untreated (TUT).

\[\begin{split}ATE & = E [Y_1 - Y_0]\\ TT & = E [Y_1 - Y_0 | D = 1]\\ TUT & = E [Y_1 - Y_0 | D = 0]\\\end{split}\]

The relationship between these parameters depends on the assignment mechanism that matches agents to treatment. If agents select their treatment status based on their own benefits, then agents that take up treatment benefit more than those that do not and thus TT > TUT. If agents select their treatment status at random, then all parameters are equal. The policy relevance of the conventional treatment effect parameters is limited. They are only informative about extreme policy alternatives. The ATE is of interest to policy makers if they weigh the possibility of moving a full economy from a baseline to an alternative state or are able to assign agents to treatment at random. The TT is informative if the complete elimination of a program already in place is considered. Conversely, if the same program is examined for compulsory participation, then the TUT is the policy relevant parameter. To ensure a tight link between the posed policy question and the parameter of interest, Heckman and Vytlacil ([13]) propose the policy-relevant treatment effect (PRTE). They consider policies that do not change potential outcomes, but only affect individual choices. Thus, they account for voluntary program participation. Policy-Relevant Average Treatment Effects The PRTE captures the average change in outcomes per net person shifted by a change from a baseline state \(B\) to an alternative policy \(A\). Let \(D_B\) and \(D_A\) denote the choice taken under the baseline and the alternative policy regime respectively. Then, observed outcomes are determined as

A policy change induces some agents to change their treatment status (DB != DA), while others are unaffected. More formally, the PRTE is then defined as

In our empirical illustration, in which we consider education policies, the lack of policy relevance of the conventional effect parameters is particularly evident. Rather than directly assigning individuals a certain level of education, policy makers can only indirectly affect schooling choices, e.g. by altering tuition cost through subsidies. The individuals drawn into treatment by such a policy will neither be a random sample of the whole population, nor the whole population of the previously (un-)treated. That is why we estimate the policy-relevant effects of alternative education policies and contrast them with the conventional treatment effect parameters. We also show how the PRTE varies for alternative policy proposals as different agents are induced to change their treatment status.

Local Average Treatment Effect¶

The Local Average Treatment Effect (LATE) was introduced by Imbens and Angrist ([20]). They show that instrumental variable estimator identify LATE, which measures the mean gross return to treatment for individuals induced into treatment by a change in an instrument.

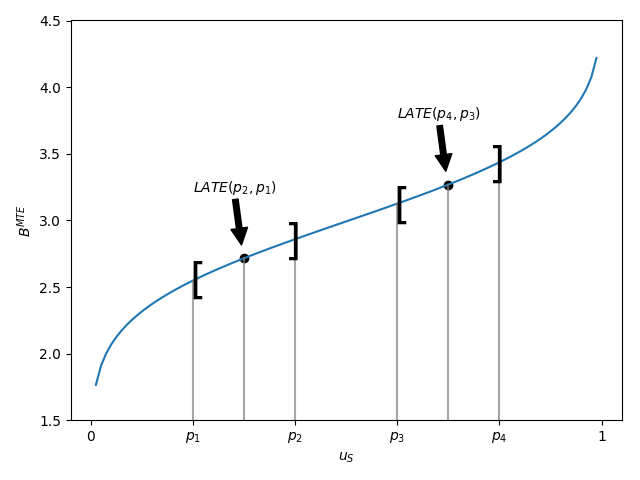

LATE at different values of \(u_S\)

Unfortunately, the people induced to go into state 1 \((D=1)\) by a change in any particular instrument need not to be the same as the people induced to to go to state 1 by policy changes other than those corresponding exactly to the variation in the instrument. A desired policy effect may bot be directly correspond to the variation in the IV. Moreover, if there is a vector of instruments that generates choice and the components of the vector are intercorrelated, IV estimates using the components of \(Z\) as the instruments, one at a time, do not, in general, identify the policy effect corresponding to varying that instruments, keeping all other instruments fixed, the ceteris paribus effect of the change in the instrument. Heckman develops this argument in detail ([9]).

The average effect of a policy and the average effect of a treatment are linked by the marginal treatment effect (MTE). The MTE was introduced into the literature by Björklund and Moffitt ([3]) and extended by Heckman and Vytlacil ([13], [14], [15]).

Marginal Treatment Effect¶

The MTE is the treatment effect parameter that conditions on the unobserved desire to select into treatment. Let \(V = E[U_C - (U_1 - U_0) | I ]\) summarize the expectations about all unobservables determining treatment choice and let \(U_S = F_V (V)\). Then, the MTE is defined as

The MTE is the average benefit for persons with observable characteristics \(X = x\) and unobservables \(U_S = u_S\). By construction, \(U_S\) denotes the different quantiles of \(V\) . So, when varying \(U_S\) but keeping \(X\) fixed, then the MTE shows how the average benefit varies along the distribution of \(V\) . For \(u_S\) evaluation points close to zero, the MTE is the average effect of treatment for individuals with a value of \(V\) that makes them most likely to participate. The opposite is true for high values of \(u_S\). The MTE provides the underlying structure for all average effect parameters previously discussed. These can be derived as weighted averages of the MTE ([14]).

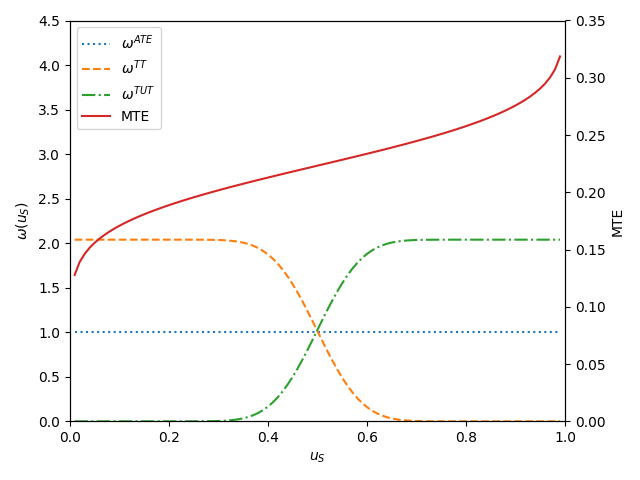

Parameter \(j, \Delta j (x)\), can be written as

where the weights \(hj (x, u_S)\) are specific to parameter j, integrate to one, and can be constructed from data.

Weights for the marginal treatment effect for different parameters.

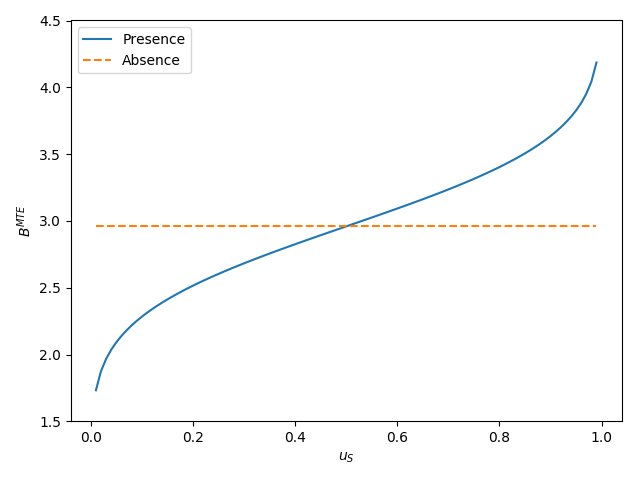

All parameters are identical only in the absence of essential heterogeneity. Then, the \(MTE(x, u_S)\) is constant across the whole distribution of \(V\) as agents do not select their treatment status based on their unobservable benefits.

MTE in the presence and absence of essential heterogeneity.

So far, we have only discussed average effect parameters. However, these conceal possible treatment effect heterogeneity, which provides important information about a treatment. Hence, we now present their distributional counterparts ([1]).

Distribution of Potential Outcomes¶

Several interesting aspects of policies cannot be evaluated without knowing the joint distribution of potential outcomes (see [2] and [11]). The joint distribution of \((Y_1, Y_0)\) allows to calculate the whole distribution of benefits. Based on it, the average treatment and policy effects can be constructed just as the median and all other quantiles. In addition, the portion of people that benefit from treatment can be calculated for the overall population \(Pr(Y_1 - Y_0 > 0)\) or among any subgroup of particular interest to policy makers \(Pr(Y_1 - Y_0 > 0 | X)\). This is important as a treatment which is beneficial for agents on average can still be harmful for some. The absence of an average effect might be the result of part of the population having a positive effect, which is just offset by a negative effect on the rest of the population. This kind of treatment effect heterogeneity is informative as it provides the starting point for an adaptive research strategy that tries to understand the driving force behind these differences ([18], [19]).